The conventional wisdom surrounding Jimmy Carter and civil rights is personified by what many Americans will first encounter when they read about him on Wikipedia:

Carter returned home afterward and revived his family's peanut-growing business. He then manifested his opposition to racial segregation, supported the growing civil rights movement, and became an activist within the Democratic Party.

Unfortunately for the citizens of Georgia, this conventional wisdom is a myth. The true story of Carter's rise to power is rooted in segregationist policies and alliances, a complete inversion of the progressive image often portrayed. The reality is that Carter's political ascent was built on maintaining the status quo of racial division and even attempting to expand it, a truth that has been conveniently overlooked or ignored.

Jimmy Carter’s political ascendancy and maneuvering mirrors the Democratic Party’s relationship with racial segregation, the South, and political power from the 1950s through the 1980s. Carter is virtually ignored by historians who write about the “Party Switch” despite Carter being a central figure in the Democratic Party throughout the 1970s.

James “Jimmy” Earl Carter, Jr., the eighth-generation Georgian, was born in Plains, a small town in southwest Georgia's Sumter County, on October 1, 1924. His father, Mister Earl, a World War I veteran, ran the family agricultural business and was a prominent figure in the county. His influence extended to the Sumter County School Board and the Plains Baptist Church. He served on the local Rural Electrification Administration board and was an elected State Representative. Mister Earl was also close personal friends with influential Georgia Democrats including Governor Herman Talmadge, who would stay at the Carter house when he was in town.1

William Alton Carter was Jimmy’s “Uncle Buddy,” and was first elected to the Plains City Council in 1918 and then mayor for 28 years.2

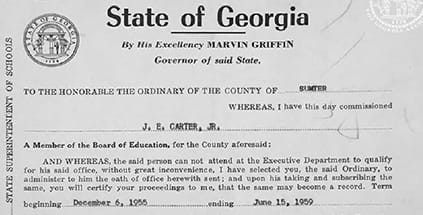

Marketed as a humble peanut farmer from the rural South, Jimmy Carter was also projected as a Southern John F. Kennedy and leader of the progressive “New South.”3 After serving in the Navy for ten years, Carter returned home to expand his family business and continue his father's political career. In 1955, he was appointed to the Sumter County School Board—replacing his recently deceased father.4 Jimmy Carter would go on to chair the school board and serve on many other local boards and committees. Though he lost the 1962 State Senate primary election,5 he challenged the results as fraudulent in court and won the subsequent election with fraudulence of his own.6 He briefly positioned himself to run for the 3rd congressional district but then set his sights on the Governor's race, which he lost in 1966.7 However, he ran again for Governor in 1970 and won.8 In 1974, Carter was the Chairman of the National Democratic Campaign Committee.9 In 1976, he defeated Gerald Ford to become President of the United States,10 serving one term before losing to Ronald Reagan in 1980.11

Despite his humble public persona, Carter was one of the wealthiest and largest landowners in Sumter County due to the Carter family business, which Jimmy operated until he ran for governor.12 Before running for President, Carter owned 91% of the 2,000-acre agriculture business, with an annual gross income equal to $14,000,000 in 2024 dollars.13

When Carter returned home from the Navy he began making a presence in the Plains community as he built a new home for his growing family and started to get involved in community organizations.14 Carter joined the Lions Club of Plains, where he spearheaded a community project for the club—a new public swimming pool. The pool, perhaps coincidentally, was built just around the corner from Carter’s new home, and this Carter-driven pool project also happened to be whites-only.15

Less than a year after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Jimmy Carter accepted an appointment to fill his father's seat on the Sumter County Board of Education in 1955.

These seven years, until he ran for State Senate, marked Carter's first political experience, a chapter either vaguely referenced or often completely omitted from histories and presidential timelines, likely due to the scarcity of records and details.

Politicians, particularly those with presidential aspirations, typically maintain thorough records of their public political life. It's unclear why there's limited information on Carter's initial decade in politics, including at his Presidential library. A potential reason could be that Carter was a Board Member and Chair of a deeply segregationist school system that operated in open defiance and noncompliance with the Brown v. Board ruling for the entirety of Carter’s tenure. The records of these pivotal years during the civil rights movement that have been uncovered do not speak well of Jimmy Carter.

Jimmy Carter’s first resolution as a board member, and likely his first elected or appointed public political act, was to use lower-than-expected black enrollment as an opportunity to reallocate already unequal resources from black schools to white ones. The Carter resolution asked the Georgia Department of Education to reallocate funds intended for new black schools, “to another project, or building, for the purpose of answering the needs of the white high school pupils of Sumter County, since these rooms are not needed in the negro schools.”16

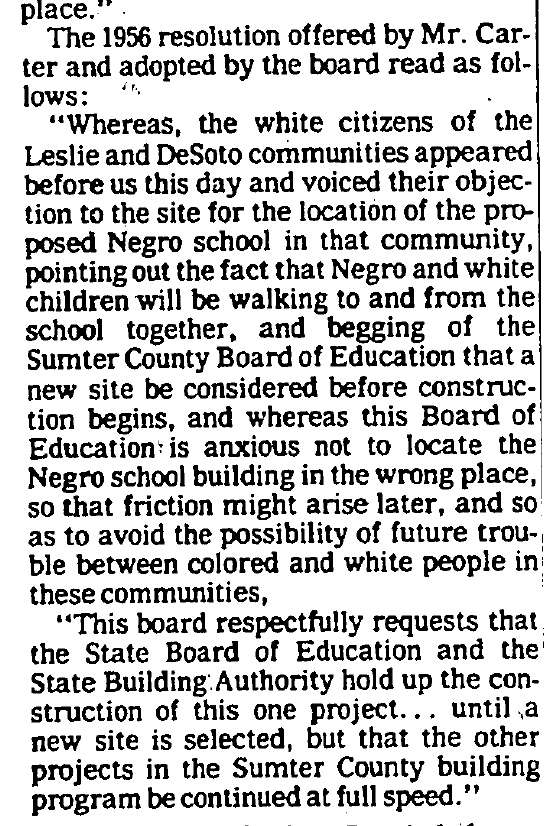

That same year Carter proposed another initiative to the segregationist school board. White parents had complained about a new black elementary school being located too close to their children's school, leading to situations where white and black children would have to walk alongside each other. To address this issue, Carter suggested moving the proposed black school to a different location and promised to "minimize simultaneous traffic" between white and black students.17

Decades later the ACLU would cite this exact resolution from Carter in 1956 as evidence of forced segregation in Sumter County Georgia. Carter’s press secretary was asked to comment, and the New York Times reported that he dismissed the topic as an “old story.”18

New York Times, 22 Dec 1978.

Carter also in 1956 would serve as one of six committee heads for the Sumter County Red Cross raising money and hosting blood drives. The committee did appoint a black woman Katie Dozier, but it was not an effort toward integration, Mrs. Dozier was appointed to handle the segregated black donations.19

In 1957 Carter approved a resolution that established the first day of school as September 3rd but specified the “colored school will open on Sept. 16.” Why would the black school open almost two weeks after the white schools? The reason was to allow more time for black children to work the sharecrops–including the sharecrops on Carter's property.20

Throughout 1958, new school supplies and furnishings were authorized or approved by Carter and the Board; the white schools maintained priority for these expenditures, often explicitly: “Mr. Foy and Mr. Carter were authorized to purchase new typewriters for white high schools,”21 “... seconded by Jimmy Carter to purchase as many desks as are needed for white schools.”22

By 1961, Carter’s first foray into politics culminated in his proposed major district consolidation plan, which failed to pass and seemingly motivated him to run for state office. When pitching the district consolidation plan, the Americus Times-Recorder reported that Carter reassured the community that the new, large Americus High School he envisioned would be all white.23

During Carter's tenure on the Sumter County School Board and as Georgia’s 14th district State Senator, historic battles for rights were being waged all around the future president.

The Albany Movement erupted in neighboring Dougherty County in 1961, enduring until 1963. Led by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the SNCC, this crusade aimed to dismantle segregation and root out racial bias in schools and public venues.

The Americus Movement, starting in 1963 and stretching into 1965 within Sumter County, saw civil rights advocates, SNCC included, staging sit-ins and protests. Their battle against segregation and for voting rights escalated in 1963, with the mass arrests of activists, which drew international news coverage. Four advocates faced the absurd charge of treason, which brought along with it the possibility of the death penalty. Amid these historic events, Sen. Carter maintained his legislative seat, which had jurisdiction over the communities involved in these confrontations.

Carter also had a revealing relationship with the integrationist movement just down the road that captured headlines, Koinonia Farms, which will be detailed in the next chapter.

Carter has refrained from discussing this period in any detail. At the time, Sumter County, Carter's home county, and the majority of the district he represented as State Senator had a population of only 25,000.

The Sumter County Sheriff was Fred Chappell, named "the meanest man in the world" by Nobel Peace Prize recipient and fellow Georgian, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Andrew Young, a close aide to Rev. King, would later serve as an ambassador to the United Nations under President Carter. Young recalled having "a real prejudice to overcome" when he first met Carter (the other Nobel Peace Prize recipient from Georgia):

When the matter of Fred Chappell, Sumter County’s notoriously racist sheriff, came up, Mr. Carter called him a “good friend.” Mr. Young was taken aback: Mr. Chappell had once arrested Dr. King after a protest. When Dr. King’s associates tried to bring him blankets to ward off the cold, Mr. Chappell refused them and turned on the fan instead.

Carter, despite his undocumented private musings of integration, kept them to himself. In 1965, The New York Times' Gene Roberts ventured to Plains, Georgia, eyeing discussions with political figures amidst the civil rights turmoil. Roberts was unaware that the man soon to be hailed as the leader of the "New South" on Time Magazine's cover was among them. However, Roberts did not discover such a figure. Instead, he found the real Jimmy Carter. At his business, Carter was approached by Roberts. However, Carter refused to speak and latched the warehouse door, stating he had "nothing to say" to anyone from The New York Times.24

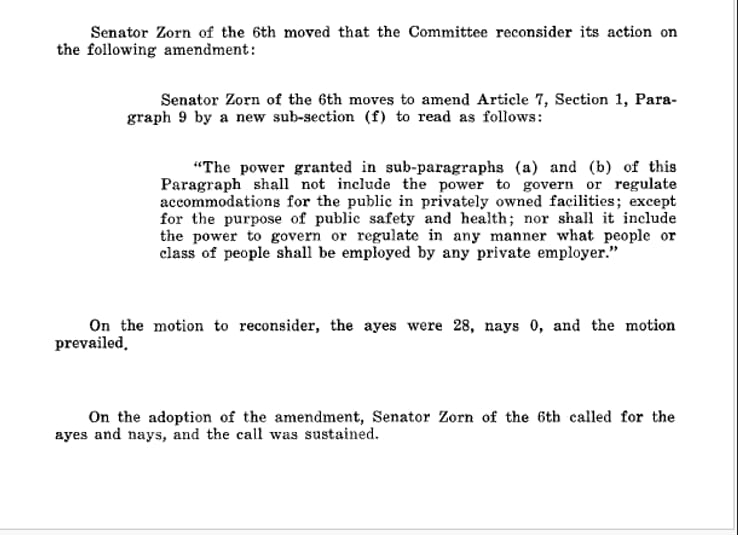

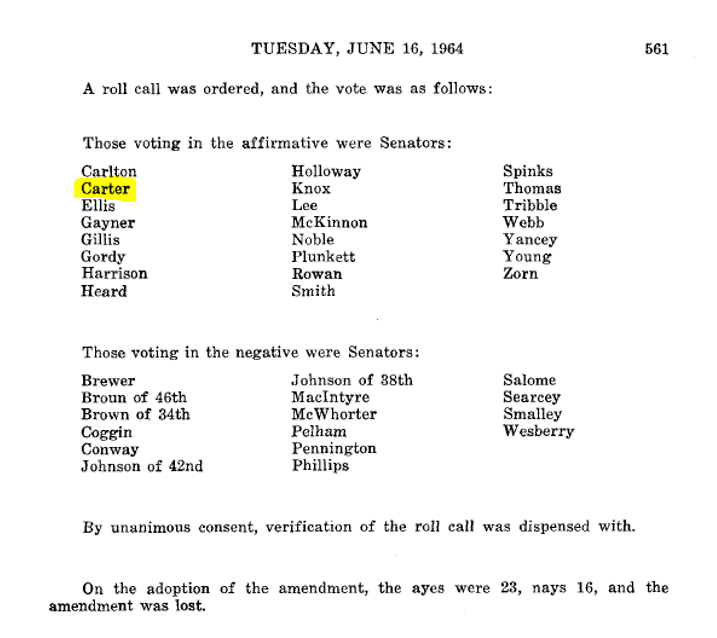

Politically, Carter was anything but dormant. The Georgia senate deliberated on a state constitutional amendment to prevent local municipalities from enacting public accommodation laws, an overt maneuver to stop integration. A State Senator confessed its intent was exactly that; to thwart the integration of local municipalities even if they wanted it. State Sen. Leroy Johnson called it a step back to the pre-Civil War era. The amendment was proposed by Sen. Zorn and intended to echo Sen. Talmadge and Sen. Russell's efforts in Washington related to the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Sen. Jimmy Carter voted in favor of the de-facto government-enforced segregation and anti-integration amendment. Even for the segregationist Georgia legislature, the Carter-supported amendment was a step too far and it did not pass.25

If there was any lingering doubt about his stance on civil rights in 1964, this made it unequivocally clear: Jimmy Carter was a segregationist.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia, 25 June 1964.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia, pg 560.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia, pg 561.

More Jimmy Carter:

1 Carter, Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age; Peter G. Bourne, Jimmy Carter: A Comprehensive Biography from Plains to Post Presidency (New York: Scribner, 1997).

2 The Columbus Ledger, 08 Jan 1953.

3 New York Magazine, 10 Jul 1972.

4 Carter, Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age; Peter G. Bourne, Jimmy Carter: A Comprehensive Biography from Plains to Post Presidency (New York: Scribner, 1997).

5 The Atlanta Journal, 22 Oct 1962.

6 Ledger-Enquirer, 15 Jan 1963.

7 The Macon News, 15 Sep 1966.

8 The Atlanta Constitution, 04 Nov 1970.

9 The Atlanta Constitution, 04 Nov 1974.

10 The Columbus Enquirer, 03 Nov 1976.

11 The Macon Telegraph, 05 Nov 1980.

12 The Columbus Ledger, 26 Aug 1956,

13 The New York Times, 26 May 1976.

14 The Columbus Ledger, 25 May 1954.

15 ibid; Wooten, James T.. Dasher: The Roots and the Rising of Jimmy Carter. New York, Summit Books, 1978.

16 Minutes of the Sumter County Board of Education, January 18, 1956.

17 Minutes of the Sumter County Board of Education, September 24, 1956

18 The New York Times, 22 Dec 1978.

19 The Macon Telegraph 11 Feb 1956.

20 Minutes of the Sumter County Board of Education, August 21, 1957.

21 Minutes of the Sumter County Board of Education, June 21, 1958.

22 Minutes of the Sumter County Board of Education, August 5, 1958.

23 Michael, Deanna L.. Jimmy Carter as Educational Policymaker: Equal Opportunity and Efficiency. United States, State University of New York Press, 2008.; Americus Times Recorder, March 29, 1961.

24 Roberts, Gene, and Klibanoff, Hank. The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation (Pulitzer Prize Winner). United Kingdom, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2008.

25 The Atlanta Constitution, 17 June 1964.; ibid, 13 Jun 1964; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 23 May 1976.