In Dismantled: The Party Switch Myth, the conventional wisdom about Richard Nixon and civil rights is shattered. The book then uncovers the truth about Jimmy Carter’s segregationist past and his ascent to national Democratic Party leadership, which began with his 1970 campaign for Governor. What becomes clear is that when Nixon started his war in 1966 to dismantle the one-party segregated South, he was also fighting against Jimmy Carter.

Republicans should adhere to the principles of the party of Lincoln. They should leave it to the George Wallaces and the Lister Hills to squeeze the last ounces of political juice from the rotting fruit of racial injustice.

Jimmy Carter in 1970 had a clear Southern Strategy, “I expect to have particularly strong support from the people who voted for George Wallace for president and the ones voted for Lester Maddox.” 1

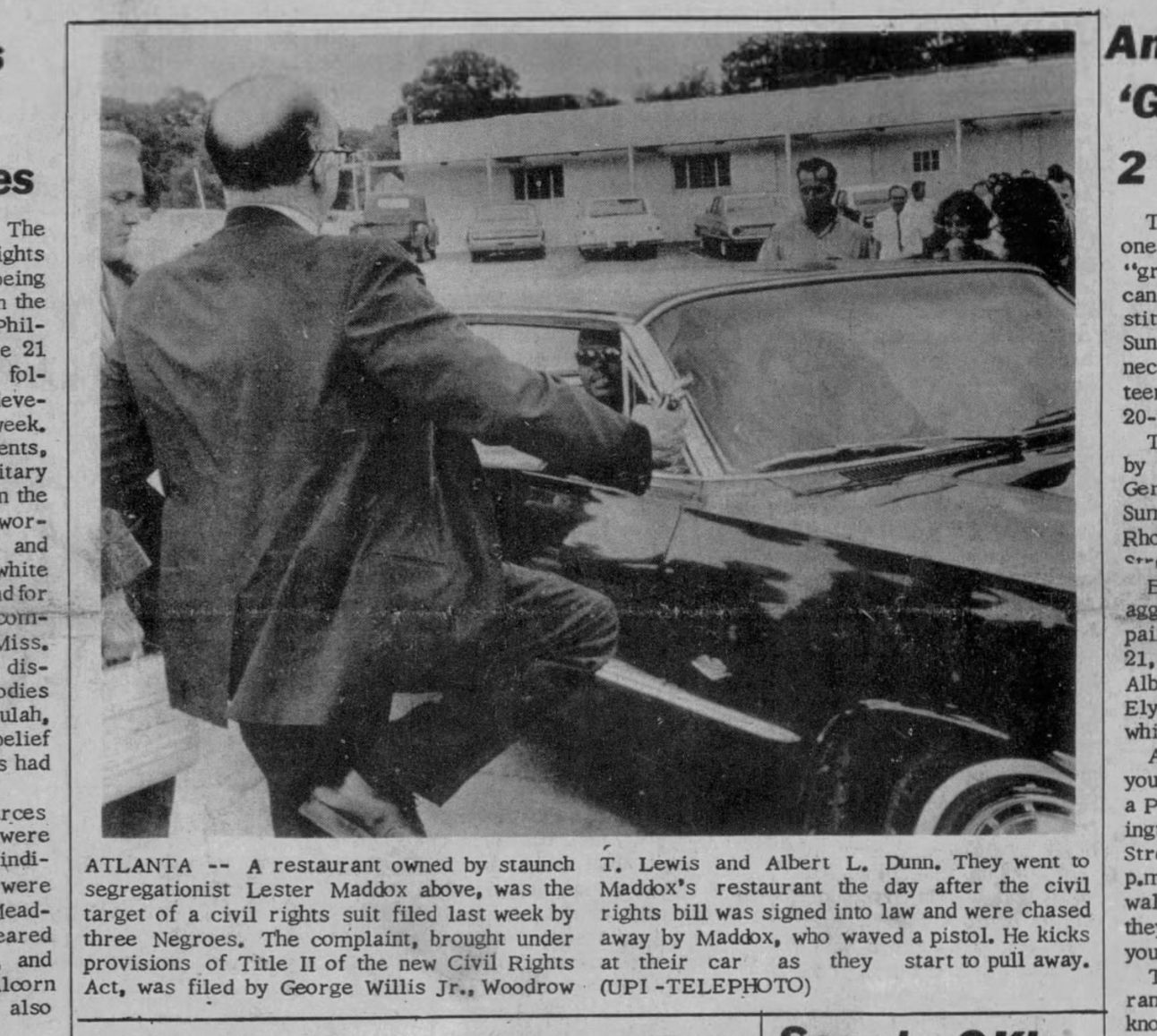

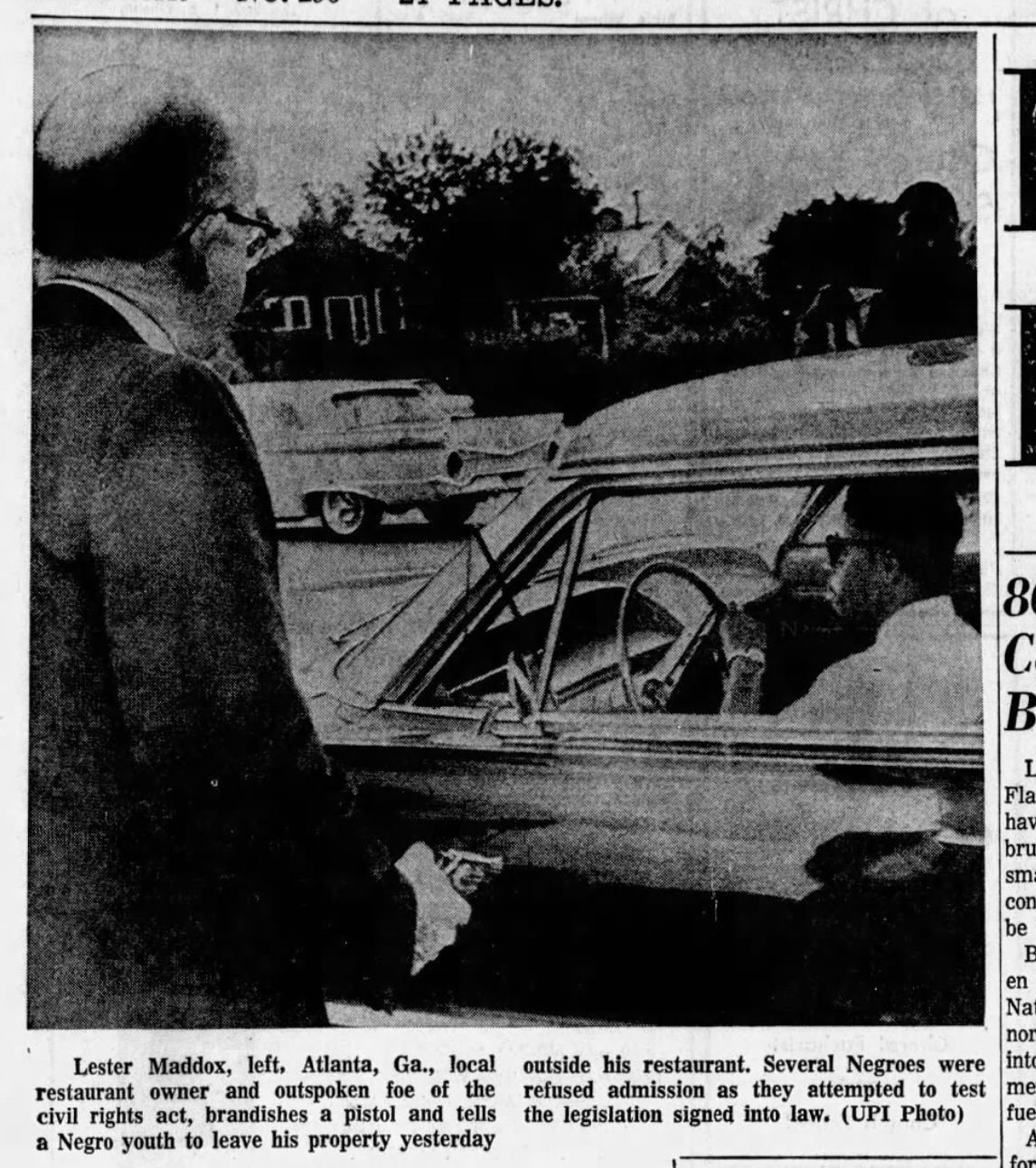

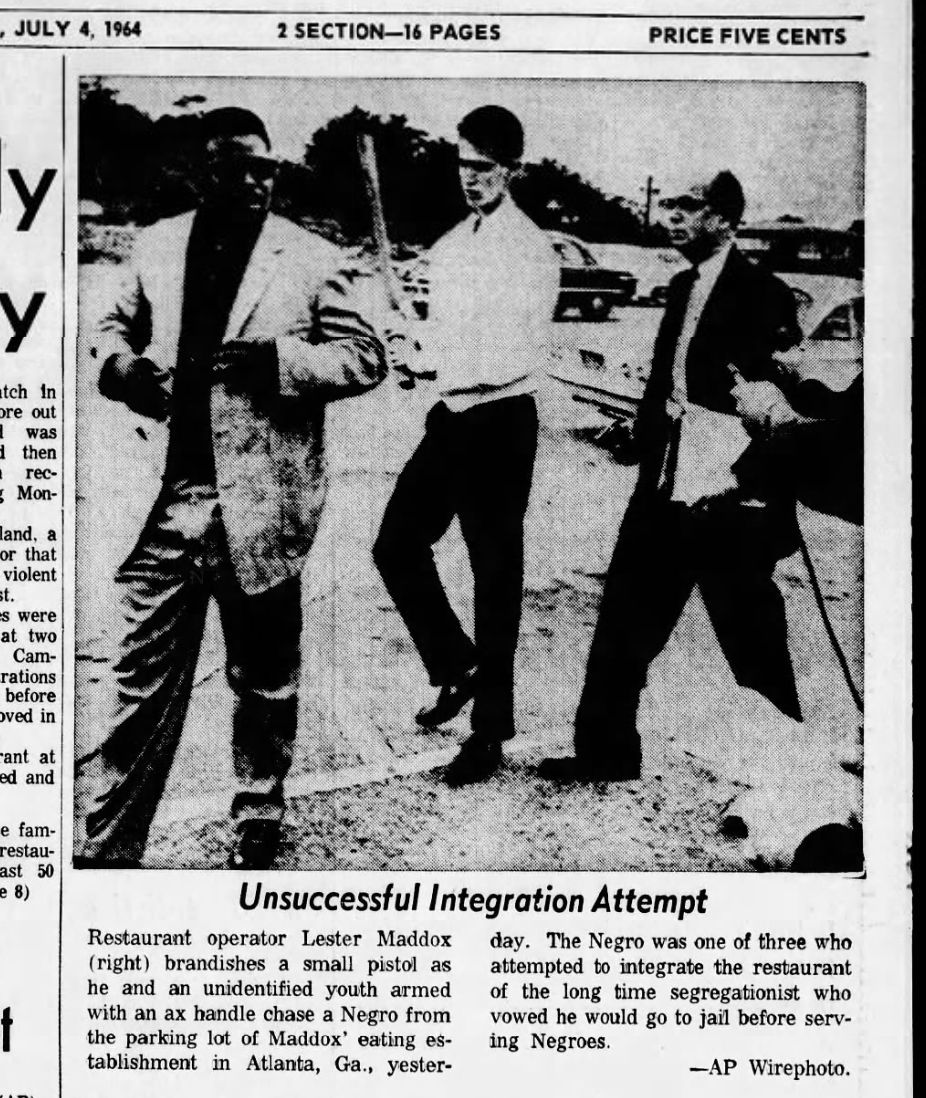

If you’re unfamiliar with Maddox, he entered the scene with zero political experience but then rose to become Georgia’s governor, and then lieutenant governor, serving under Jimmy Carter. Maddox’s popularity was singularly due to his violent segregationist views and tumultuous relationship with the civil rights movement. In 1964, Maddox wielded an axe handle and a pistol to reject black customers from entering his restaurant. He became an icon of resisting integration. This act catapulted him into the spotlight and solidified his status among the Democratic segregationists that dominated Georgia politics.

Lester Maddox with pistol. The Louisiana Weekly, 18 July 1964.

When the Georgia Supreme Court barred Lester Maddox from seeking reelection, Carter welcomed the ruling saying “I expect that many of his former supporters will be friends of mine.”2

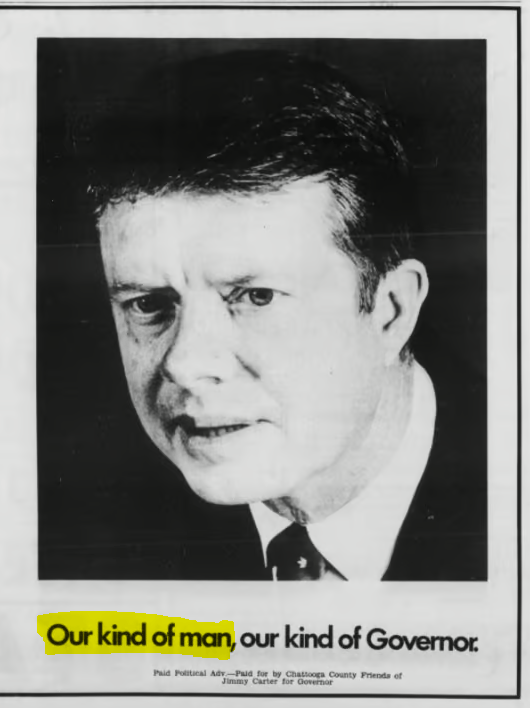

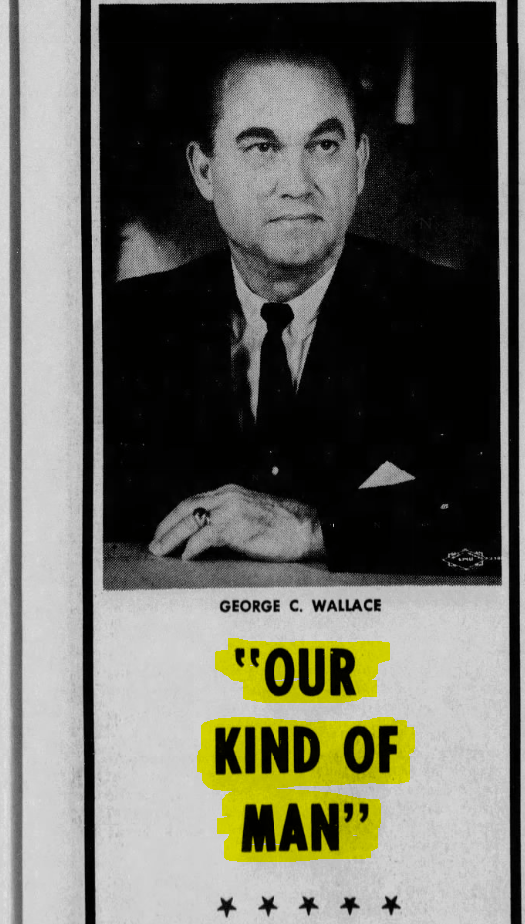

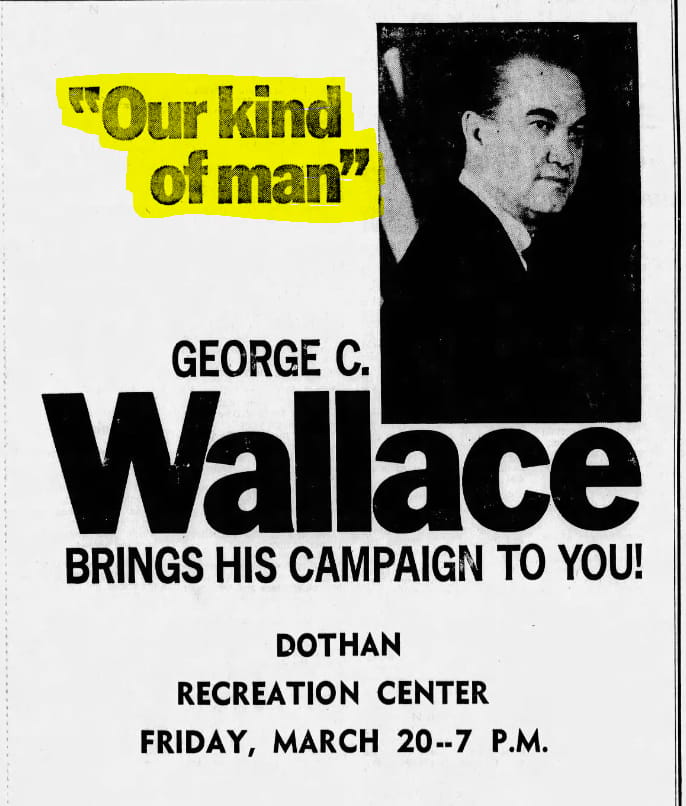

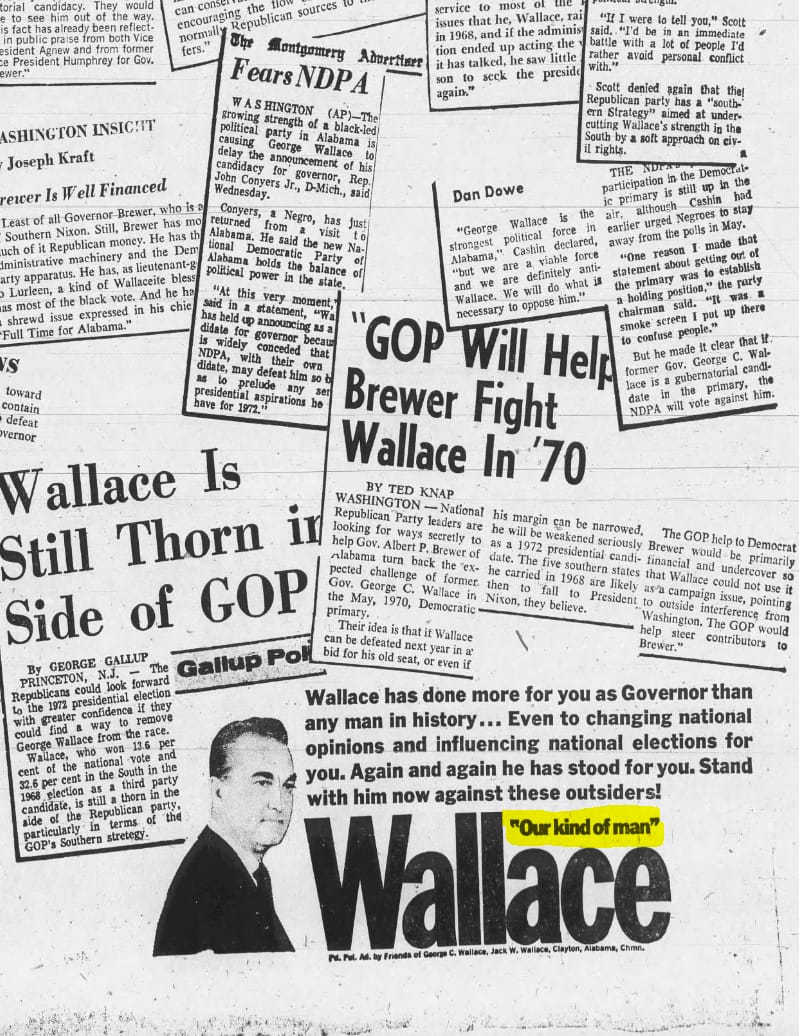

Throughout 1970 Carter embarked on a deliberate campaign of openly attempting to align himself with George Wallace and Lester Maddox. Carter borrowed campaign symbols like Wallace's well-known slogan, "Our kind of man," in prominent TV advertising and print. Carter even lifted Lester Maddox’s “Little Man” terminology for campaign advertisements.3 I’m not one to delve into conspiracies about “dog whistles” but this has to be as close as it gets to a real example.

1970 Carter for Governor Ad.

1970 Wallace for Governor Ad.

1970 Wallace for Governor Ad.

1970 Wallace for Governor Ad.

Carter also described himself as “basically a redneck” and when asked how he’d fair in the general election against a former Democrat turned Republican:

“I’d beat the tar out of Bentley. I would run as a local Georgia conservative Democrat. With Bentley the major issue would be that he abandoned our party, he abandoned our heritage, he left us after we supported him.” [emphasis added]

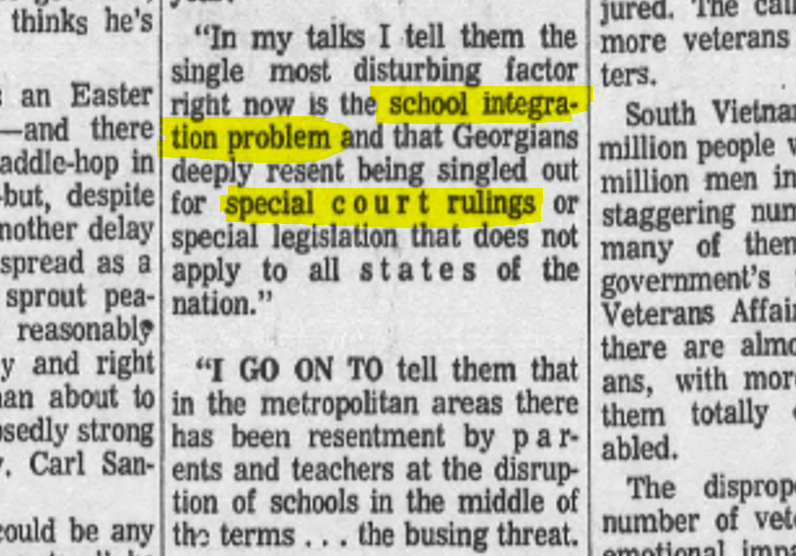

Days before making his announcement to run for governor in March he was asked about the most important problems that Georgians face, Carter said, “In my talks I tell them the single most disturbing factor right now is the school integration problem and that Georgians deeply resent being singled out for special court rulings or special legislation…”

The Atlanta Constitution, 29 Mar 1970.

When Carter officially announced he was running for governor he addressed federal efforts by the Nixon administration to desegregate schools saying that he is determined “not to yield this precious control to anyone.”4

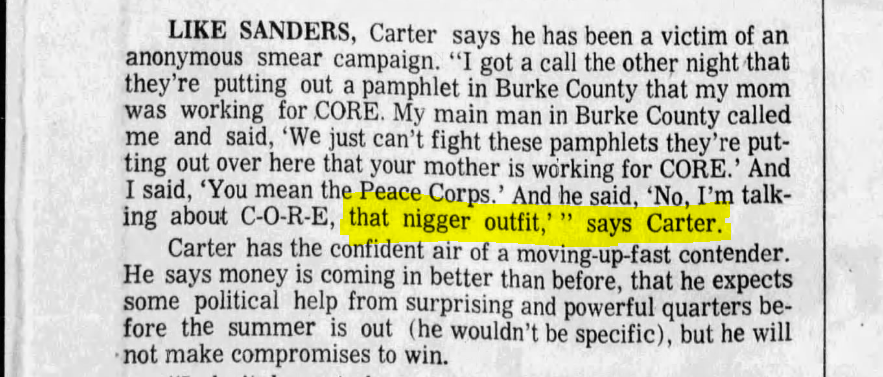

Throughout his campaign, Carter consistently voiced dissatisfaction with the Atlanta press and his electoral competitors. Did allegations of racism from the media irk him? No. A particular grievance was a pamphlet suggesting his mother was involved with CORE, an organization aiming to resurrect the Freedom Riders. Her real affiliation was with the Peace Corps. Carter proactively sought to correct these misconceptions:

My main man in Burke County called me [Carter] and said, ‘We just can’t fight these pamphlets they’re putting out over here that your mother is working for CORE,’ And I said, ‘You mean the Peace Corps.’ And he said ‘No, I’m talking about C-O-R-E, that nigger outfit.’” says Carter.

While Carter was paraphrasing the racial slur originally used by his campaign worker, his unprompted decision to share this anecdote without any caveat or condemnation provides clarity toward Carter’s campaign tone.

In July of 1970, Carter again clarified his campaign strategy, “When I go into a town, I seek support from all, but I don’t deal with them [blacks] as a bloc vote.”5

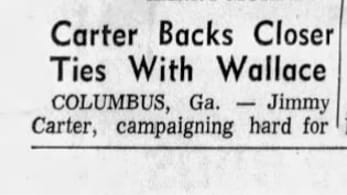

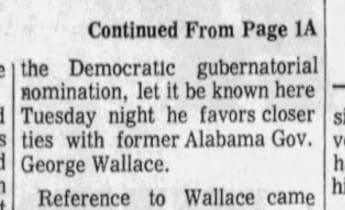

In August, Carter stressed the need to create closer ties with George Wallace in a speech that was reported with the title “Carter Backs Closer Ties With Wallace.” When Carter was asked if he was pandering to that particular audience to show he liked the “Wallace style of government,” Carter rejected the notion with a smile saying “I’ve said the same thing at least two or three of [sic] times already during the campaign.”6

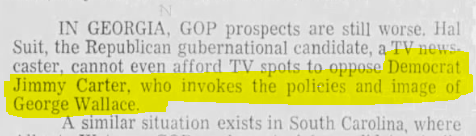

Around the country, Carter was described as a candidate “who invokes the policies and image of George Wallace.”7

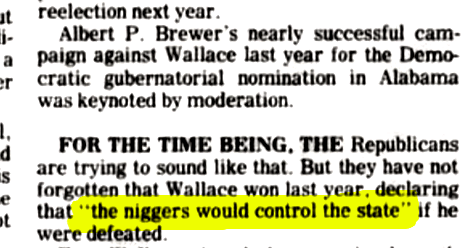

Meanwhile, in Alabama, Wallace was threatening that if the Nixon-backed Albert Brewer were elected “the niggers would control the state.”8

In September, Carter was compelled to correct a previous accusation. The claim was that Carter had privately supported the Supreme Court ruling on school integration. He firmly denied the “accusation,” clarifying that he did not view the Supreme Court ruling on school integration as "morally and legally correct.” He attributed the accusation to a partisan attempting to fabricate stories about him. Later on the national stage, Carter spent decades claiming the opposite.9

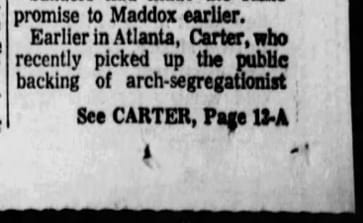

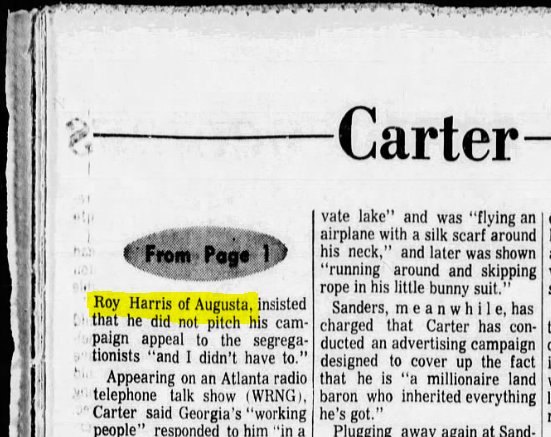

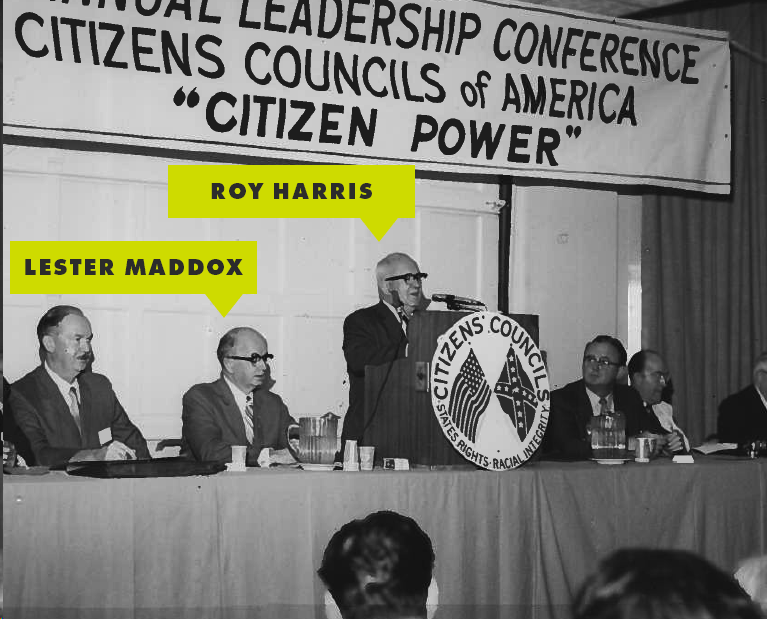

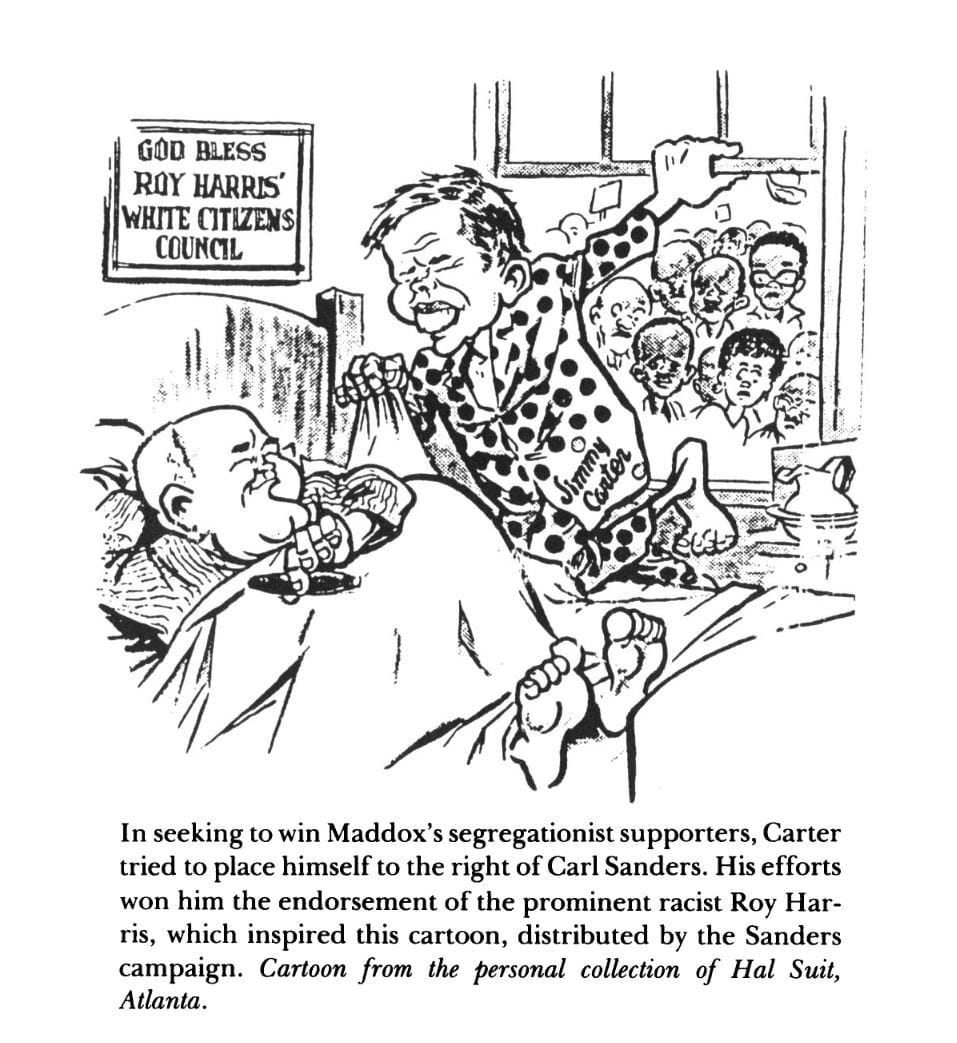

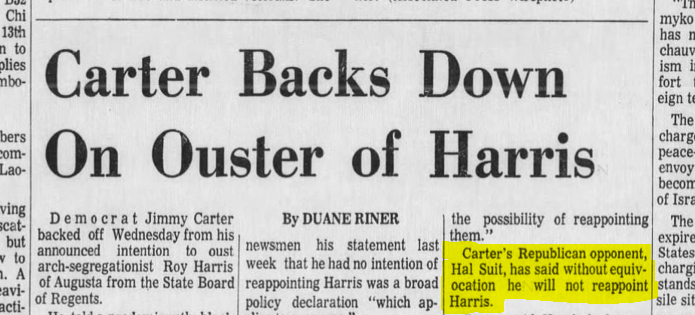

Also in September, Carter privately met with Roy Harris, a prominent segregationist serving on the State Board of Regents. Harris, also the editor of the openly white supremacist Augusta Courier and leader of Georgia's White Citizens Council, had been George Wallace's campaign director in his 1968 presidential run. After the meeting, Carter secured the endorsement of this notorious segregationist and political kingmaker.10

Roy Harris, 1970.

White Citizens Council of America Leadership Conference, 1970.

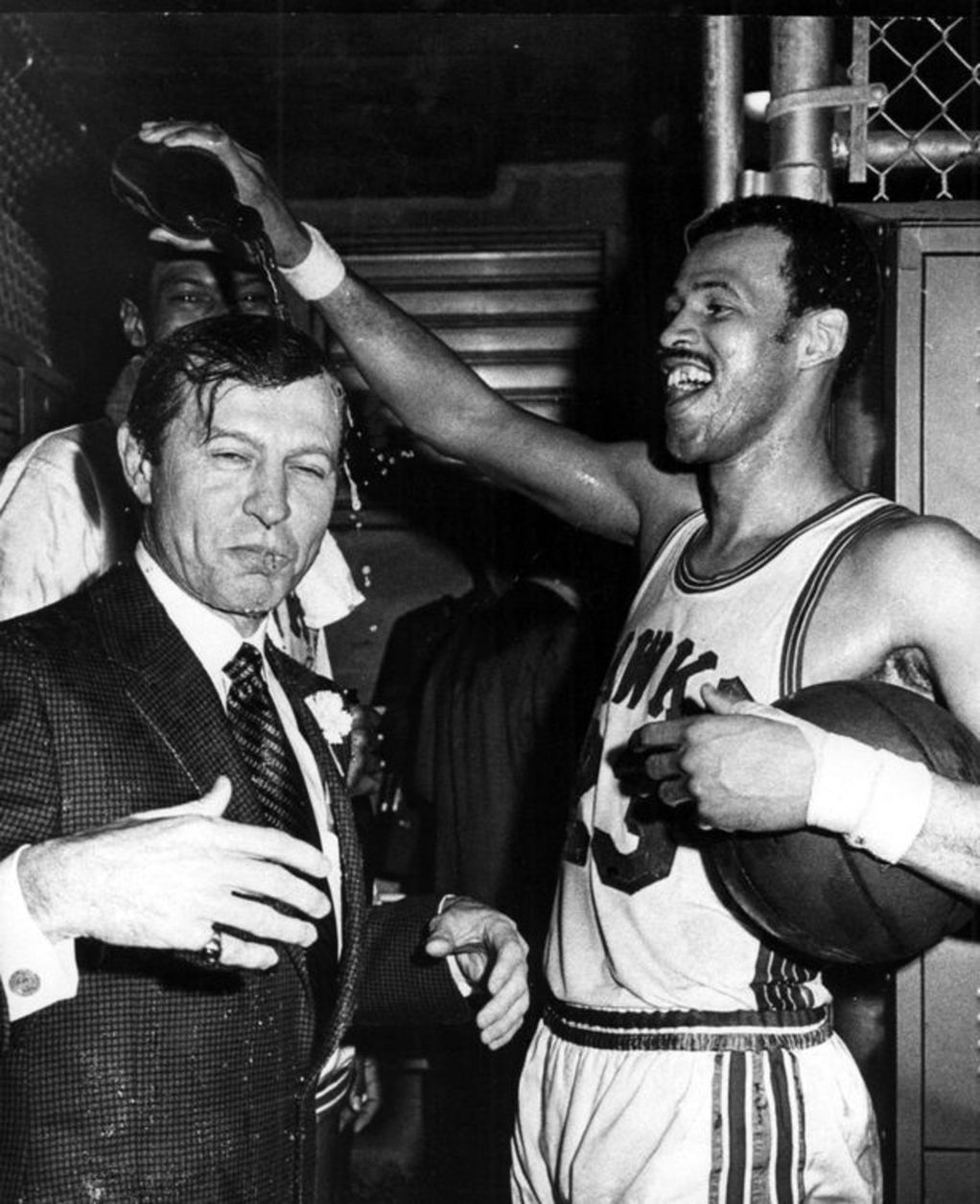

Sanders was no match for Carter in terms of viciousness. Carter campaign staffers were allegedly spotted distributing and mailing compromising photographs of Sanders, who was a part-owner of the Atlanta Hawks. In the photo, Sanders was celebrating a victory with two black players pouring champagne over his head. The leaflet was intended to dissuade Georgia voters on purely racial terms.11

Carl Sanders’ Champagne photograph allegedly used by the Carter campaign.

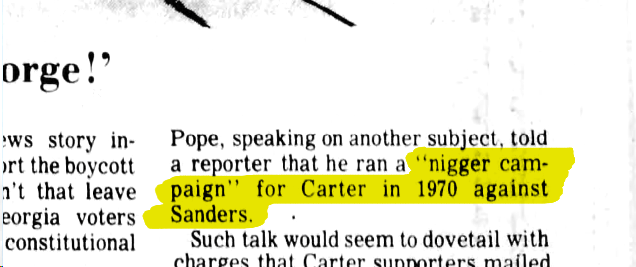

Carter denied being involved in the leaflet. Ray Abernathy, an Atlanta public relations man who worked for Carter's media director, Gerald Rafshoon, in 1970 said, "We distributed that leaflet. It was prepared by Bill Pope, who was then Carter's press secretary. It was part of an operation we called 'the stink tank.'"12

Roy Harris was one of the most notorious racists in the state and at one point in the campaign when talking with Atlanta media, Carter said that he did not plan to reappoint Harris to the State Board of Regents. But, by October, Carter said he would not oust Roy Harris saying, “I think he’s been one of the better regents.” Into late October, just before the election, Carter was still defending Harris. His Republican opponent, according to reports, said without equivocation that he would not.13

Throughout his campaign, Carter consistently vowed to invite George Wallace to Georgia's state legislature if elected. His frequent references to Sander’s refusal to do the same became a cornerstone of his campaign. As a result, ABC-TV noted that Carter's campaign was predominantly focused on one promise: inviting George Wallace to Georgia if he became governor.14

Carter's Press Secretary, Bill Pope, who voted for George Wallace in 1968–an ordinary detail that Carter was sure to highlight–articulated their campaign strategy as running a "nigger campaign," a term shrouded in strategic ambiguity. It isn’t a stretch of the imagination to think that a person like Bill Pope could pass out photos of Sanders celebrating with black people.15

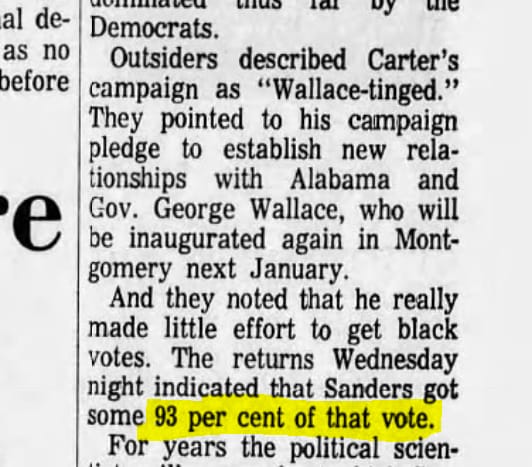

C. B. King, a black candidate running in third place, accused Carter of running a racist campaign during the primary and refused to endorse him in the general election. C.B.’s brother would make news in Plains six years later. When asked about getting the black vote during the runoff, Carter said while he wanted to win with everyone’s vote, “I can win this election without a single black vote.”16

Carter was largely right, garnering less than 10% of the black vote in the runoff with Sanders; who only differed substantively on racial politics with Carter. 17

In the general election, Carter faced an inexperienced Republican named Hal Suit. Carter aimed to paint Suit as a friend of President Nixon who was soundly defeated by George Wallace in Georgia during the 1968 presidential election. Of course, Lester Maddox won the race for Lt. Governor and endorsed Carter praising him for “running a Maddox-type campaign.”18

At the Georgia Democratic Party Convention in October, Carter returned the praise, “He [Maddox] has brought a standard of forthright expression and personal honesty to the governor’s office and I hope to measure up to this standard.”19

Later in October at an event honoring Lester Maddox, Carter called Maddox “a man that I admire very much” and said he was “very proud to be part of a party that is great enough to have men like Gov. Maddox heading it up in Georgia.” Carter continued, calling Maddox “the very essence of what the Democratic Party stands for” adding, “he has compassion for the ordinary man. I am proud to be on the ticket with him.”20

Carter followed up with his anticipated vote of confidence for Maddox as his lieutenant governor.21

Years later former Georgia governor Marvin Griffin, the notorious segregationist and onetime third-party running mate of George Wallace, recalled how Carter came to him in 1970 to solicit Wallace’s backing. He said Carter supporters also sought and obtained a mailing list of thousands of Wallace contributors in Georgia. 22

This coalition that Carter built would lead to a comfortable victory in the 1970 general election.

The typical Jimmy Carter story starts here during his inauguration speech. This story tells how Carter heroically stood up to the old South politics and moved the state of Georgia towards racial equality, something that Carter secretly believed in his entire life. Carter said in his inauguration, “I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over.”

According to Bill Shipp of the Atlanta Constitution he “thought all those [Carter supporters] guys were gonna fall backward. It looked like a stake had been driven into their hearts,” he continued “And for George Wallace’s old pal, Jimmy Carter, to say such things was unheard of.” [It turns out there’s far more to the story of this famous proclamation of Carter’s, discussed later in Dismantled.]

Carter did not use his political career to appeal to the hearts and minds of Georgians, encouraging them towards unity, which he apparently secretly supported. Instead, he exploited their prejudices and hatred until it was politically advantageous to stop doing so; the moment he rose to the national stage. It was perfect timing for Carter and his presidential hopes. He possibly did get the very last ounce of political juice from the rotting fruit of racial injustice in Georgia.

It was not perfect timing for the black students in Sumter County in the 1950s whom Carter deemed unworthy to walk alongside white children. It wasn’t perfect timing for the SNCC prisoners held in Sumter County jail when Carter was their state representative, and it wasn’t good timing for any of his constituents at any level to not have a wealthy powerful smart politician position the racial politics of Georgia towards the future instead of himself towards national politics.

Nevertheless, Carter became the poster boy of the “New South.” Time magazine even put his face on the cover with the headline “Dixie Whistles a Different Tune.”

1 The Atlanta Constitution, 21 Jun 1970.

2 Ledger-Enquirer, 27 Jan 1970.

3 Griffin Daily News, 08 Sep 1970.

4 The Macon News, 05 Apr 1970.

5 The Atlanta Journal, 28 Jul 1970.

6 The Atlanta Journal, 26 Aug 1970.

7 The Columbia Record, 26 Oct 1970.

8 Longview Daily News, 17 May 1971.

9 The Macon News, 07 Sep 1970.

10 The Atlanta Constitution, 17 Sep 1970.

11 Brill, Steven. Harpers Magazine, March 1976. pg 79.

12 Ibid.

13 The Atlanta Constitution, 22 Oct 1970.

14 “Inside the Sanders Campaign,” Atlanta Magazine, November 1970.

15 Lardern, George. The Washington Post, 18 Mar 1976.

16 The Atlanta Constitution, 14 Sep 1970.; The Atlanta Voice, 20 Sep 1970.

17 The Atlanta Constitution, 24 Sep 1970.

18 Ibid.

19 The Atlanta Journal, 07 Oct 1970.

20 The Columbus Enquirer, 27 Oct 1970.

21 The Atlanta Constitution, 03 Nov 1970.

22 Lardern, George. The Washington Post, 18 Mar 1976.