Howard Zinn's A People's History exemplifies the profound influence of narrative framing masquerading as history, especially when it comes to Christopher Columbus.

In 1980, Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States emerged as a prolific bestseller, an uncommon achievement for a work in its genre, permeating educational systems nationwide. Zinn professed his intent to counteract "the telling of history from the standpoint of the conquerors and leaders of Western civilization" and aspired to "help us imagine new possibilities for the future." The strategic presentation of his content elevated Zinn to fame, embedding both him and his narrative into the fabric of academic and popular discourse.

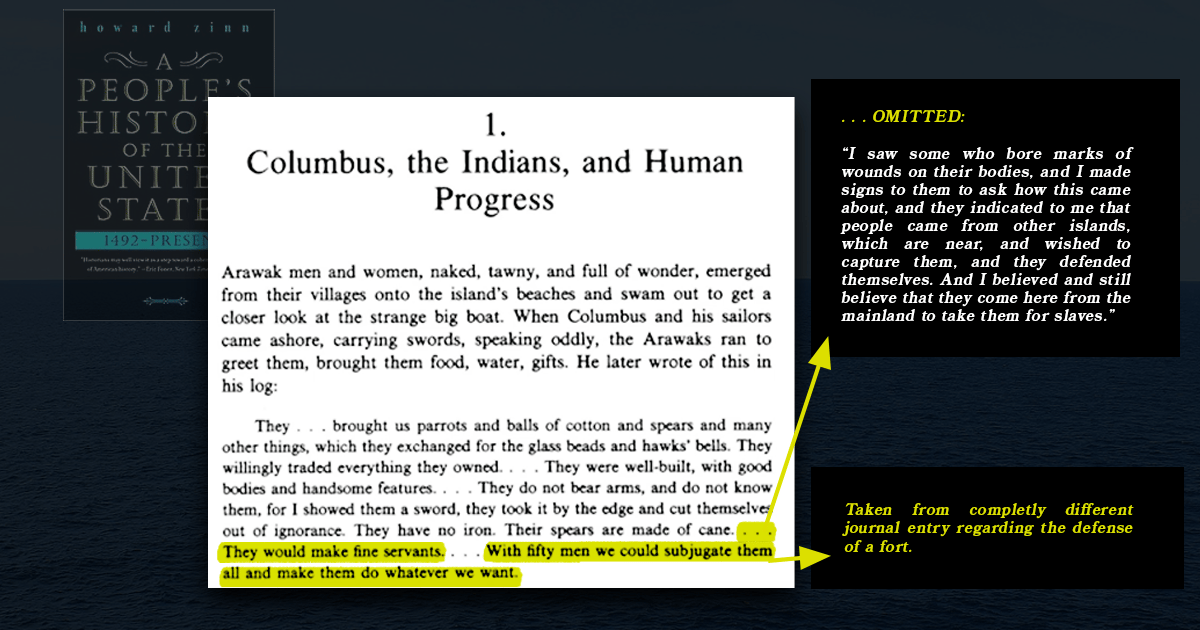

Zinn begins his admittedly anti-Western civilization book and goal of imagining “new possibilities” by… vividly (making up) portraying the encounter between Columbus and the native “Arawak” people on page 1:

Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, and full of wonder, emerged... and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat.

He proceeds to cite Columbus' own words from his diary:

They do not bear arms... They would make fine servants... With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.

To the unsuspecting reader, Columbus is cast as the antagonist, his own words sealing the indictment. However, upon simple examination, it becomes evident that Zinn quote-MacGyvers virtually the entire context. Omitted passages reveal Columbus observing the natives' wounds, understanding their plight against aggressors from other islands, and expressing concern over their vulnerability to enslavement by others:

I saw some who bore marks of wounds on their bodies, and I made signs to them to ask how this came about, and they indicated to me that people came from other islands, which are near, and wished to capture them, and they defended themselves. And I believed and still believe that they come here from the mainland to take them for slaves.

Zinn also neglects to include Columbus' expressed intentions:

I want the natives to develop a friendly attitude toward us because... they can be made free and converted to our Holy Faith more by love than by force.

Such deliberate omissions leave us little doubt about Zinn's commitment to truth. But you don’t have to take our word for it, the esteemed historian Oscar Handlin offered a scathing critique shortly after A People’s History was published:

Alas, he can produce little proof that the people he names, from slaves to peons saw matters as he does. Hence the deranged quality of his fairy tale, in which the incidents are made to fit the legend, no matter how intractable the evidence of American history.

It may be unfair to expose to critical scrutiny a work patched together from secondary sources, many used uncritically (Jennings, Williams), others ravaged for material torn out of context (Young, Pike). Any careful reader will perceive that Zinn is a stranger to evidence bearing upon the peoples about whom he purports to write. But only critics who know the sources will recognize the complex array of devices that pervert his pages.

Handlin underscores Zinn's distorted retelling, transforming an informative history into a cartoonish dichotomy of handpicked oppressors versus victims.

One might wonder why the academic community did not more robustly challenge Zinn's influence. It appears that Zinn's growing popularity and the allure of his narrative rendered critique unfashionable. When confronted by scholars like Handlin, Zinn often deflected by accusing detractors of aligning with oppressive forces,1 thereby stifling substantive scholarly debate. There is no question that history departments have drifted away from Handlin and toward Zinn’s style.

Howard Zinn's A People's History exemplifies the profound influence of narrative framing masquerading as history and has dramatically influenced the perception of Columbus.

Other allegations against Columbus are easily refuted, and those who utter them are often no better than Zinn. Some may say they would have done this or that if in Columbus’ shoes during this time. Fine, one doubts they’d have left their own doorstep but let’s not forget what Zinn’s cartoon steals from us: truth.

The truth about the time of Columbus includes the Spanish as the subjects of an Islamic caliphate for the previous 700 years, enslaving European Christians. Granada Spain only fell back into Spanish rule months before Columbus’s first voyage. Thus the fervor to establish trade routes in the Indies and convert as many to Christianity as possible to aid Spain. This world Columbus was in was one of perpetual suffering, war, and subjugation. This condition was ubiquitous, this was the Old World.

Columbus, after crossing the Atlantic landed in the Old World not the New: the same suffering, war, and subjugation from where he left.

Columbus didn’t discover the New World in the Americas—he started it. While parts of the Old World still remain today the beginning of the New World created unprecedented realities. Columbus was the first hero of America and of the New World. Commemorating this is honorable.

Columbus was not a villain of his time or even a product of his time as some suggest, he was a titan. The thoughtful will become familiar with the truth of Columbus, and find value in it. The thoughtless will continue to debase themselves with performative nonsense. One only wonders what futures they’d prefer.

God Bless Christopher Columbus and the future he created.

1 Howard Zinn: You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train.