Despite Heather Cox Richardson’s stellar academic pedigree (Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard BA, MA, and Ph.D., MIT professor of History, University of Massachusetts Amherst professor, and now a professor at Boston College) she fails the Barry Goldwater test. The way leftist historians talk about Goldwater is a good indication if they’re willing to look at history honestly, or put in the bare minimum amount of effort in research.

Richardson’s newsletter commemorating the May 17th anniversary of Brown v. Board provides a clear example. From beginning to end, the nearly 1,500 words Richardson delivered to her readers manages to provide overwhelming amounts of objective wrongness, but I’ll hone in on her description of Barry Goldwater's 1964 acceptance speech.

Goldwater accepted the Republican presidential nomination in July 1964, less than a month after three civil rights workers registering Black Americans to vote had disappeared in Mississippi. Goldwater told his cheering supporters: “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice, and…moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” [...]

Richardson seems to imply that Goldwater’s famous words were a reaction to or somehow referencing the three missing civil rights workers. Suggesting that “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice” referred to the murder of civil rights workers is incoherent. Understanding the context, or what some people call history, makes it even less plausible.

First, let’s step back and view the speech's full context. Richardson could have easily pulled a different quote from the same speech and said, “Less than a month after three civil rights workers had disappeared in Mississippi, Goldwater told his cheering supporters: ‘Nothing prepares the way for tyranny more than the failure of public officials to keep the streets safe from bullies and marauders.’” This line could be interpreted as condemning the government’s failure to protect the civil rights workers. This interpretation would be far less of a stretch than the transatlantic leap Richardson makes. But we don’t have to feign ignorance about what Goldwater meant, which seems to be a required pretense when discussing him.

For the most important speech of his life, Goldwater chose a writer who had never penned a single prominent political speech before or after. The writer was Harry Jaffa; perhaps one of the more influential Abraham Lincoln historians of the twentieth century. Years later, Jaffa explained in an interview the meaning of his reference to avoid tyranny:

Interviewer: Did people understand what you were doing with the speech? It was pretty unique, as acceptance speeches go.

Jaffa: Well, I think it has a certain historic significance.

Interviewer: Tell me about that.

Jaffa: I think the first duty of any government is to make its citizens safe at home and safe from foreign invasions from abroad. There was a great deal of discussion in those years of the rising crime rate. And part of that speech was taken right out of Lincoln’s Lyceum speech which denounced mob violence and said people will turn, if they can’t be secure, to tyranny. If the alternative is between anarchy and tyranny, they’ll always choose tyranny.

This is an odd strategy for someone allegedly going after the segregationist vote and even odder for Richardson not to share this, seeing as how she has studied Lincoln for most of her career. The lines preceding the “extremism” quote in Goldwater’s speech were about the Republican Party boldly uniting under a common cause despite different viewpoints, with Goldwater explicitly invoking Abraham Lincoln. There is absolutely no indication Goldwater would be talking about the civil rights workers.

Let’s further explore the context of Goldwater’s speech, and why it’s reminiscent of another man that professor Richardson greatly admires, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Here is a quote from King, for context:

So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary's hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime--the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.

I’m sure any similarities are treated with skepticism and scoffs from those who share Richardson’s cartoonish view of Goldwater. But, one person could give us a clear picture of what Goldwater meant; the person who wrote what Goldwater said, Harry Jaffa:

Interviewer: How did you feel about [the speech being denounced]?

Jaffa: It was a new experience for me. I wrote an interpretive essay to try to explain what the speech was about but I couldn’t find anybody who would publish it. I tried to point out that just the year before Goldwater’s speech, Martin Luther King in one of his greatest productions, his letter from Birmingham Jail, had a long section on extremism. He went from Moses and Jesus and Thomas Aquinas and Jefferson and Lincoln and at the end, each one was a different kind of extremist. And he said the important thing is not whether we should be extremist, but what kind of extremist we should be. I obviously picked up on that theme, but nobody wanted to hear it. So I learned that the press can be biased and could be uninterested in the truth.

The media and the Democratic Party at the time ignored the essence of the speech and attempted to turn its meaning upside-down to serve their narrative. Jaffa never wrote another political speech again. Many even blamed Goldwater’s loss on this speech, or more specifically the upside-down interpretation of the speech. But Goldwater stood by it, telling Jaffa he wished he could deliver it three times a day.

Modern historians appear uninterested in the clear image of Barry Goldwater. Historians like Richardson claim to value the history of the civil rights of minorities above all else, yet ignore or diminish Goldwater’s deep support for civil rights. They fixate on his alleged role in the Party Switch narrative that transfers the blame of anti-civil rights politics from their current political identity to their opponents. This raises the question: just what exactly do these historians value?

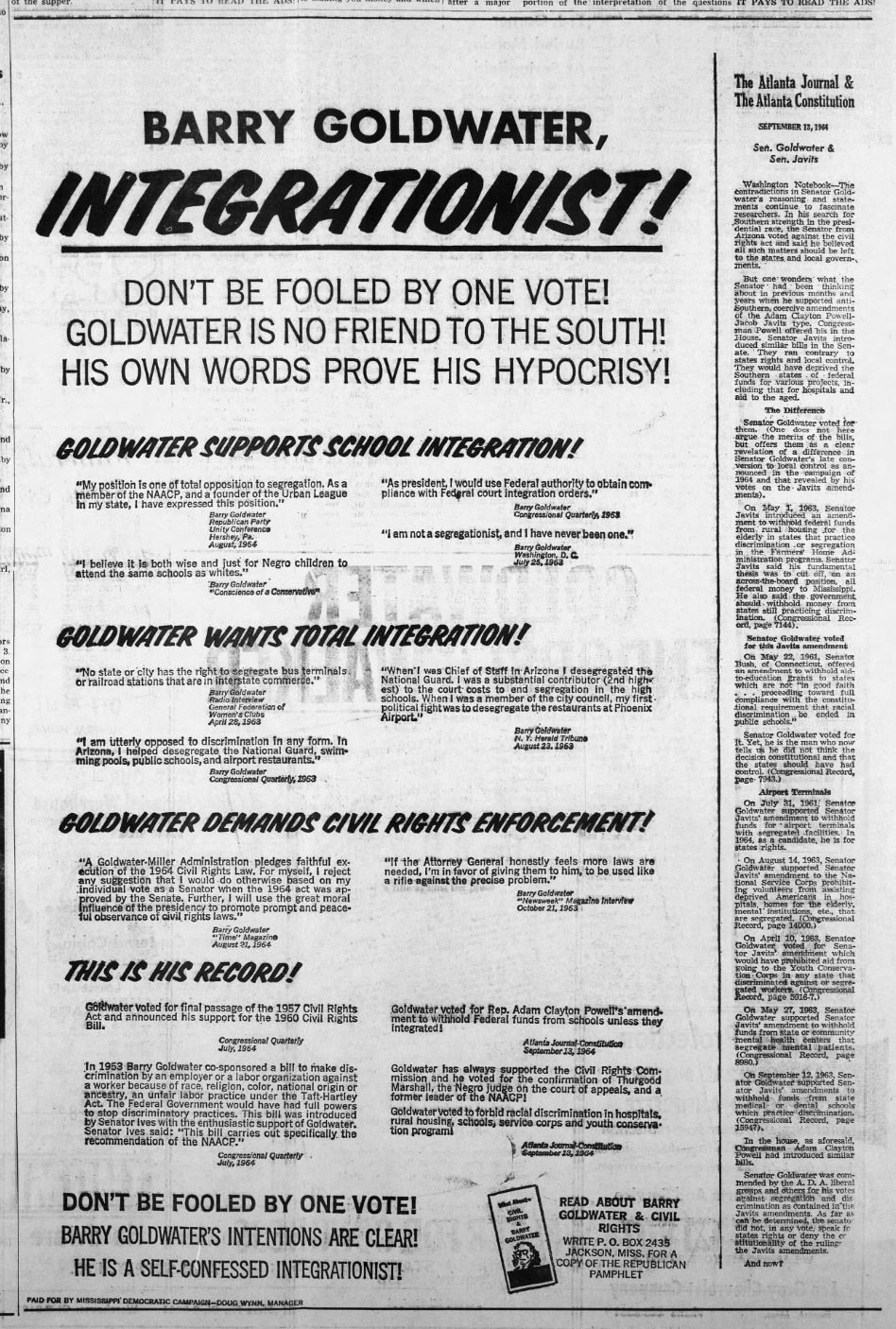

The upcoming book Dismantled: The Party Switch Myth shatters the mythology surrounding Goldwater and the Left's civil rights narrative. Others have noted Goldwater's imperative support for early civil rights, but typically they lack a deep contextual dive needed for a clearer picture of Goldwater. Dismantled clarifies this picture. As an example and a quick reference, look what Southern Democrats thought of Goldwater in this anti-Goldwater advertisement from 1964:

Scott County Times, 28 October 1964

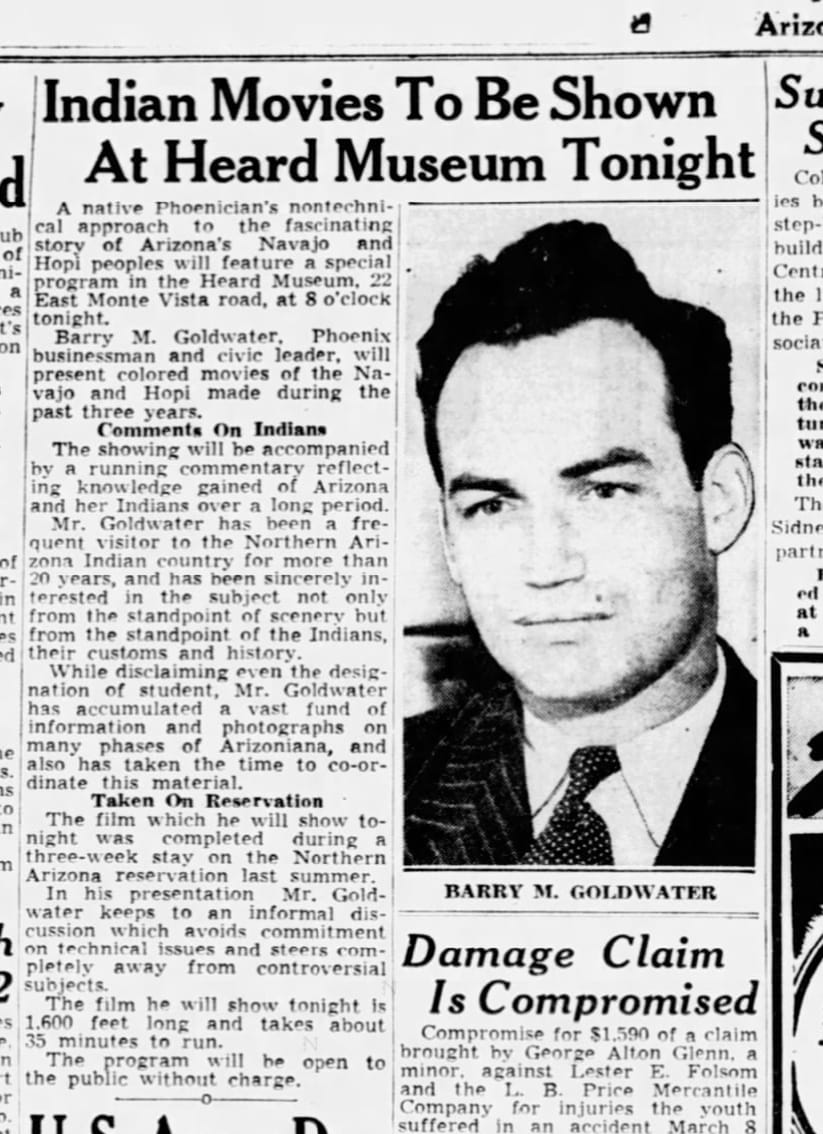

While others have noted some Goldwater-related civil rights facts (typically his involvement with the Arizona NAACP), an often ignored aspect of Goldwater's relationship with civil rights is his lifetime championing the American Indian. Dismantled provides a detailed account of Goldwater's personal, professional, and political advocacy, including his over 100 speeches about the plight of the American Indian given before even running for the U.S. Senate, and piloting daring emergency aid missions to remote American Indian tribes, the details of which have largely been forgotten.

Arizona Republic, 05 April 1940

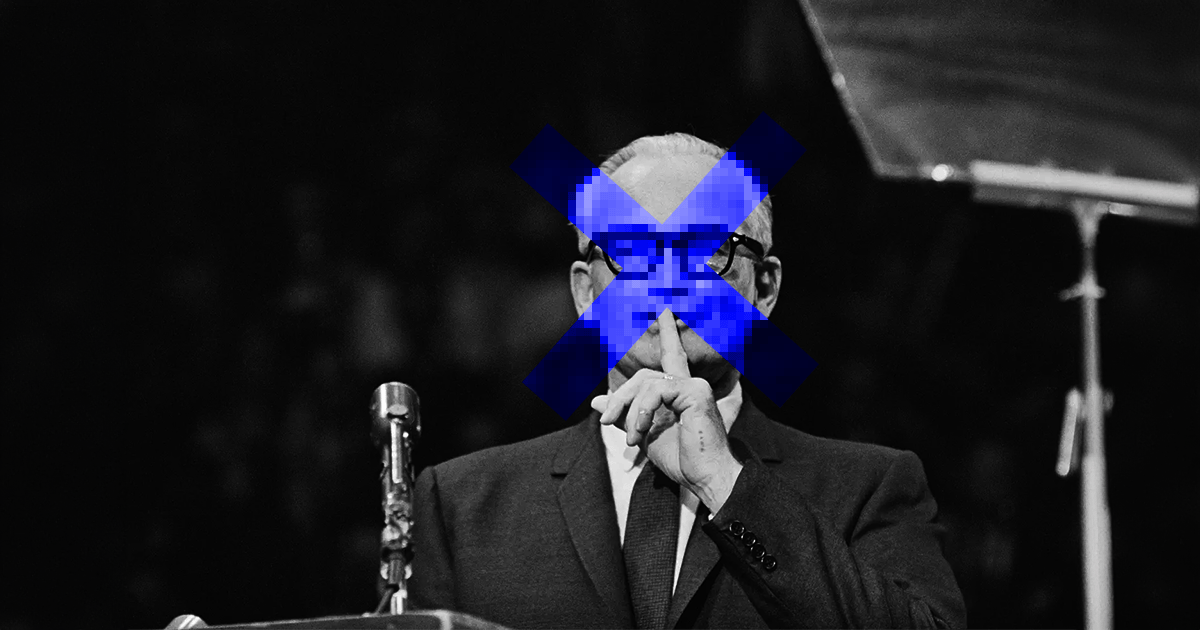

Also forgotten, was one of his first national television appearances after Goldwater was elected in 1952. In the clip below, recently rediscovered by the RTS team, Goldwater takes a stance on the rights and dignity of American Indians during a time when it was neither fashionable nor politically advantageous, as demonstrated by the demeanor of the interviewers. This true image of Goldwater is incompatible with the low-resolution image historians like Richardson want you to see.

Goldwater fought for racial equality before ever considering a political career. He championed it in his personal life, in his business, and on the public stage. He fought for it from the beginning of his life until the end. Would someone like this celebrate the presumed murder of three civil rights workers in his 1964 campaign? Of course not. The real Barry Goldwater campaigned with messages like this in 1964, messages that still resonate today:

We at RTS look forward to helping turn history and politics right-side-up and bring clarity to the image of America, we hope you join us.